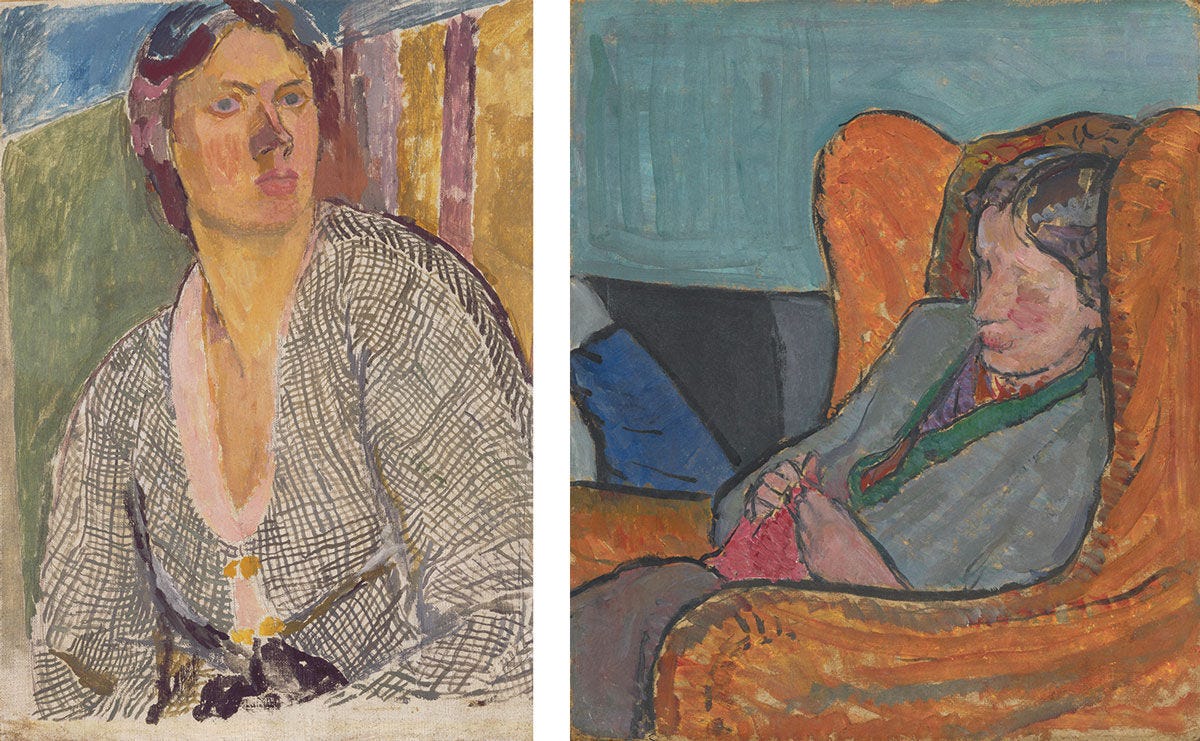

“Self-Portrait” and “Virginia Woolf” both by Vanessa Bell.

Please, to read aloud, preferably standing up (this is the first page of Woolf’s To The Lighthouse):

“Yes, of course, if it’s fine tomorrow,” said Mrs. Ramsay. “But you’ll have to be up with the lark,” she added.

To her son these words conveyed an extraordinary joy, as if it were settled, the exped…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Practicing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.