Making Yellow Heavy

(My new novel, The Float Test, comes out in April and (signed! personalized!) pre-orders are available now with my beloved Greenlight Bookstore; please feel free to order one or three if/when you’re so inclined?? You can also get it on Bookshop here.)

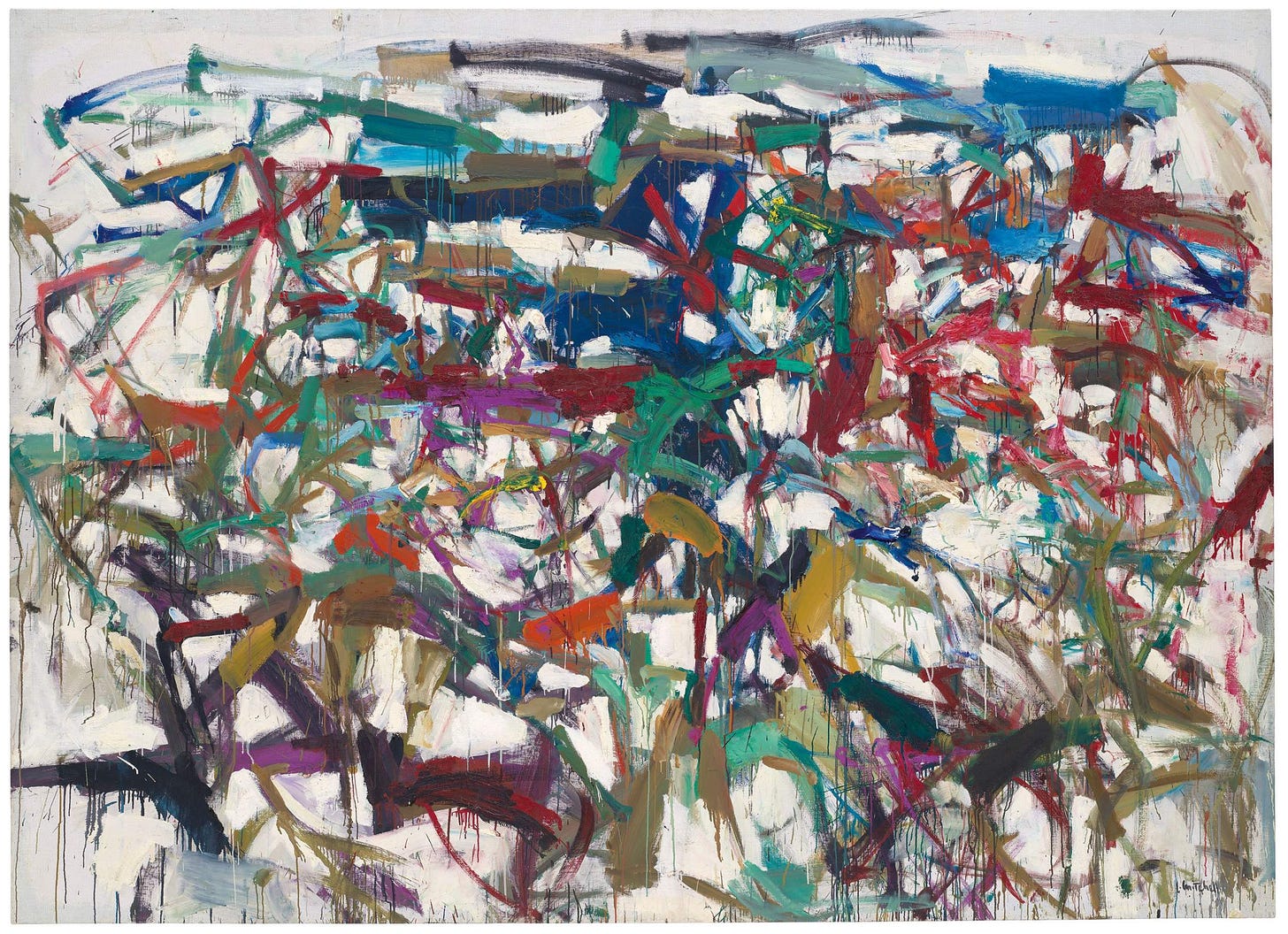

“Ladybug,” Joan Mitchell, 1957

I had picked another bit of beauty for you but then my friend sent me a s…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Practicing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.